Landmark [land-mahrk]

Noun:

- a significant event, juncture or achievement marking an important stage or turning point in something

- a prominent or distinguishing object or feature that is easily seen, especially at a distance, which serves as a guide and/or that marks a site or location

Verb (used with object):

- to declare (a building, occasion) a landmark

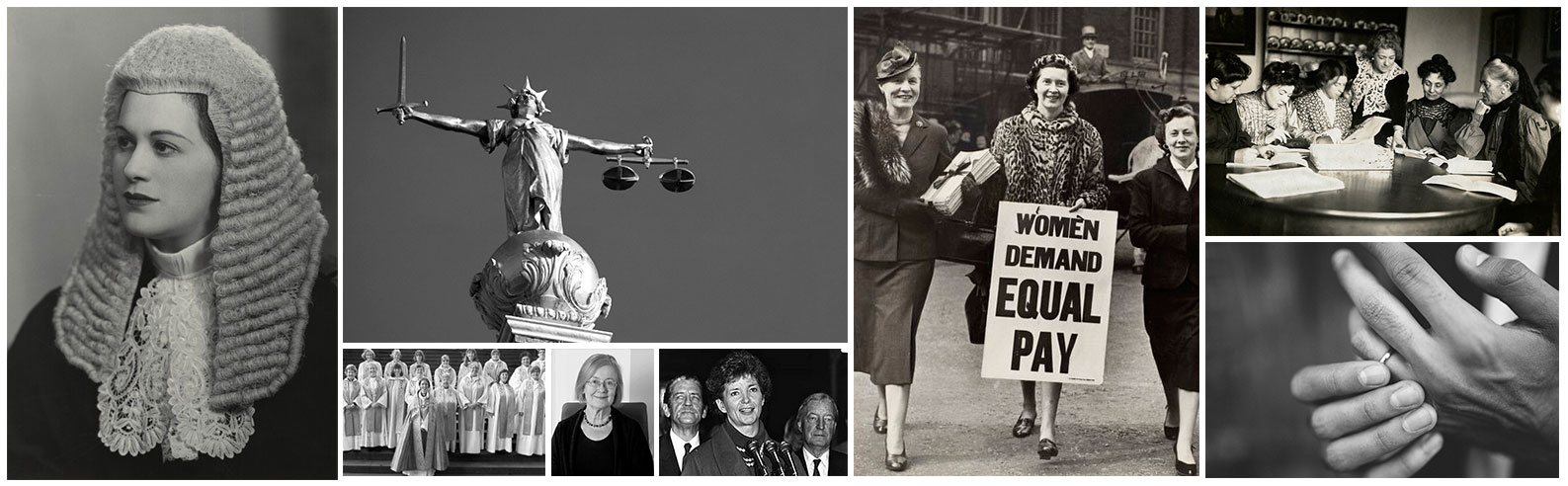

2019 marks the centenary of women’s formal entry into the legal profession. This was a key legal landmark for women. But, of course, it was not first. Feminists have long had recourse to law as a key means of achieving equality. Nor was it the last legal landmark for women. There have, and continue to be, important advances in the legal status of women. Women’s legal history is full of landmarks, turning points in law’s response to women’s lives and (diverse) experiences.

The landmarks including in the Women’s Legal Landmarks collections are a mixture of UK, English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish legal cases, and statutes and events.

While some were successful, others were less so. But all are concrete achievements, worthy of commemoration as important milestones in women’s legal history. They span eleven centuries and cover an array of topics including matrimonial property, grassroots protest, the right to vote, prostitution, surrogacy, rape, domestic violence, FGM, equal pay, abortion, twitter abuse, the ordination of women bishops, as well as short biographies of a number of ‘first woman to …’ representing the achievements of practising lawyers and legal academics from the 1880s to 2017.

Some of the landmarks are familiar steps in the history of women’s emancipation (e.g. the Married Women’s Property Acts 1870-82, Edwards v AG of Canada (1930)). Others are less familiar as feminist landmarks and/or to non-lawyers (e.g. the Gill v El Vino [1983], the Warnock Report (1984)). Similarly, while some of the stories of the first women lawyers will be familiar (e.g. Carrie Morrison, Rose Helibron, Brenda Hale), others may not be (e.g. Madge Easton Anderson, Lesley McDonagh). Together their personal histories debunk the narrative of exceptionalism and allow for exploration not only of the differences in viewpoint, ambition and feminism among women, but also their role in many of the substantive landmarks considered (e.g. Helena Normanton and the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919).

Our selection of landmarks is not comprehensive; it is not intended to be. Rather the landmarks are a reflection of the determination and commitment of – often invisible – women and groups of women in the ongoing struggle to achieve justice and equality for women.